State Duma Election, 2007

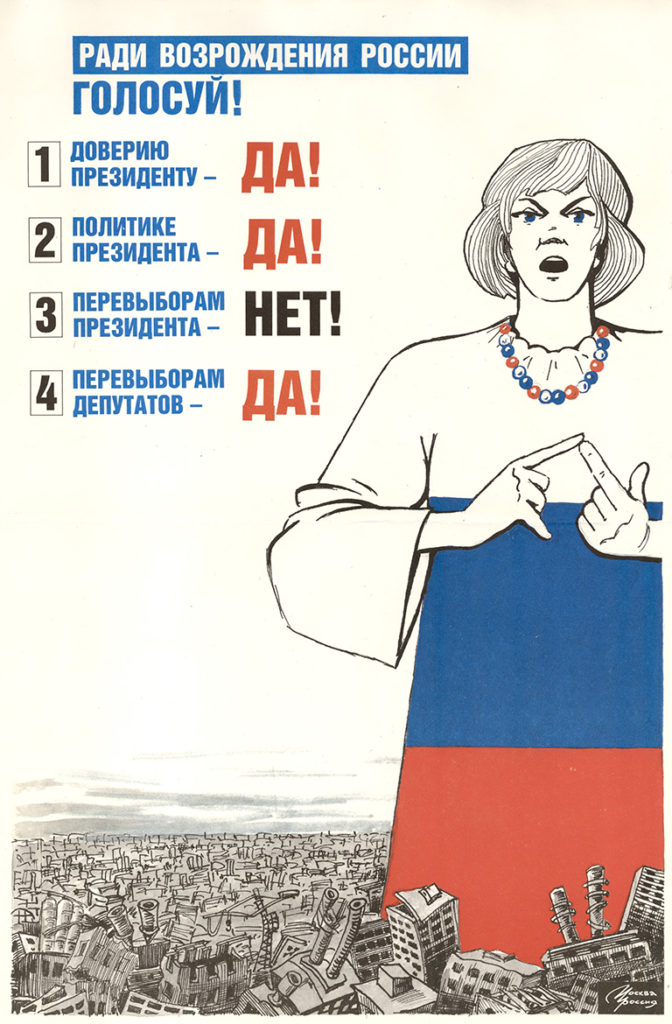

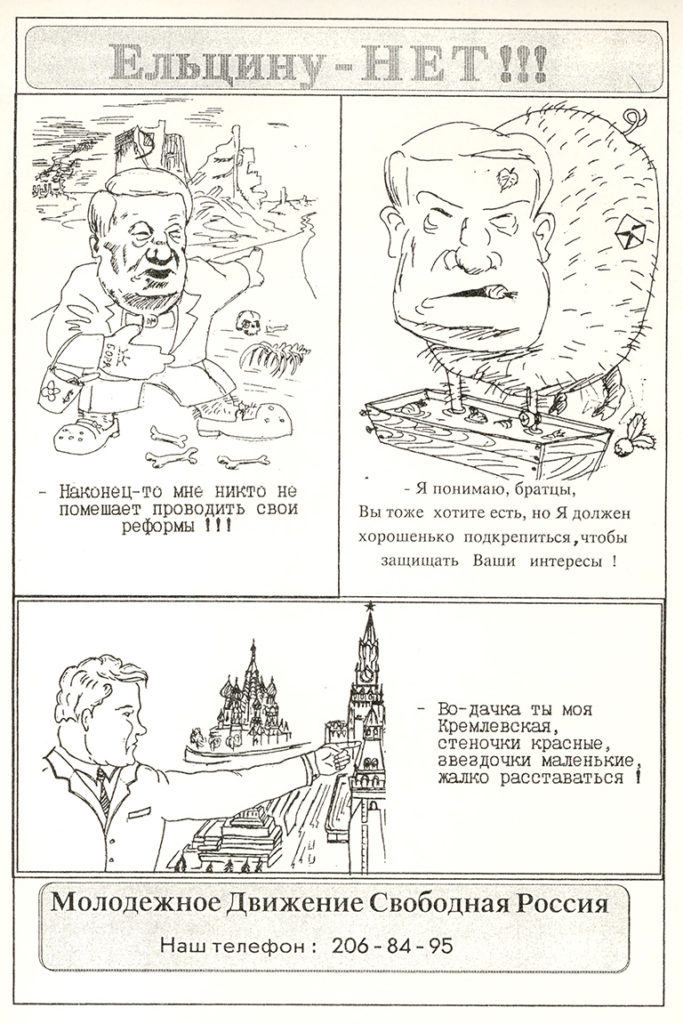

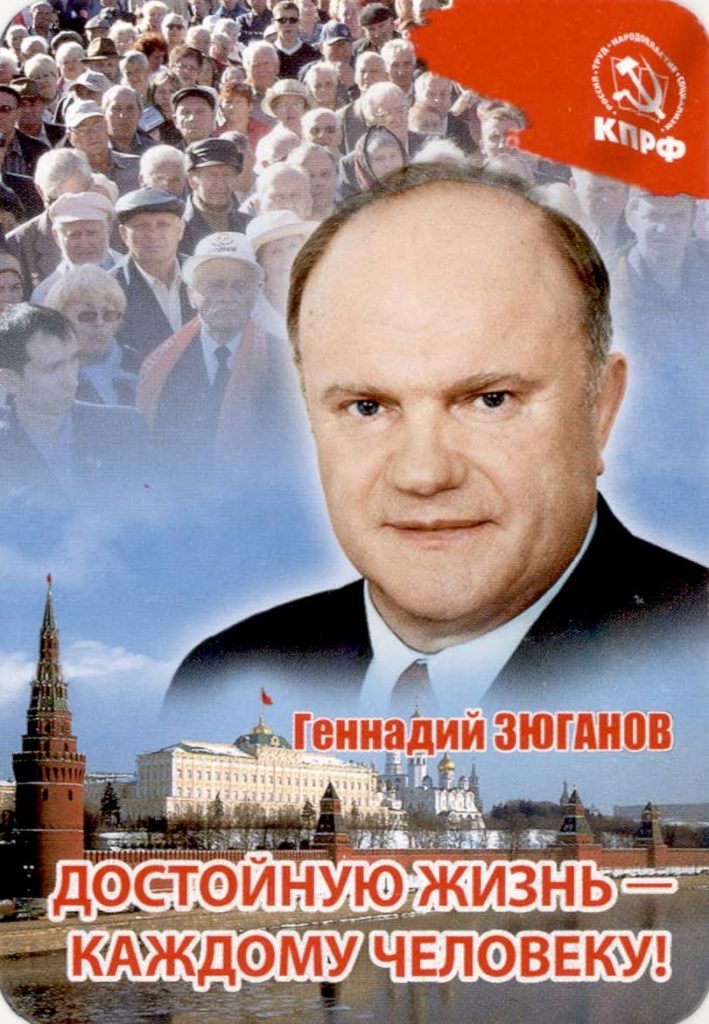

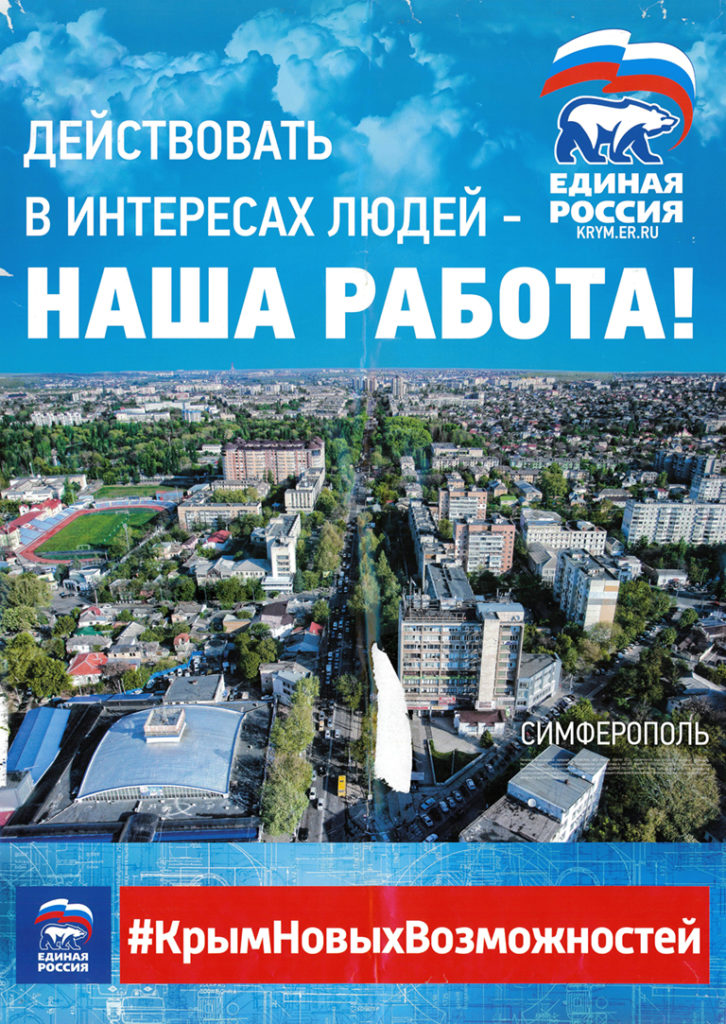

The Russian State Duma elections of 2007 took place on December 2 amid what The Economist called “Russia’s booming economy,” driven in large part by the unprecedented rise in oil and gas prices as well as robust growth in the manufacturing, construction, and trade sectors. Having successfully transitioned from the economic stagnation and political instability of the Yeltsin era, Russia experienced a period of relative political stability only to be overshadowed by the growing authoritarianism of its leader – President Vladimir Putin. Of the 16 political parties registered to participate in the elections only 11 met the Central Election Commission requirements allowing them to field candidates for the elections. As predicted by many observers, United Russia, led informally by Vladimir Putin, garnered the majority of the votes with Gennady Zyuganov’s KPRF and Vladimir Zhirinovsky’s LDPR coming in a distant second and third, respectively. The overall assessment of the elections by observers, both local and domestic, were near identical – the elections, though conducted more efficiently than in previous years, were neither fair nor free. The most common charge concerned the use of administrative resources deployed by the party in power. The media field, often lacking editorial independence, was generally in favor of United Russia.

United Russia’s win set the stage for the following year’s presidential elections that saw the emergence of the Putin-Medvedev “tandemocracy,” the power-sharing arrangement guaranteeing Vladimir Putin’s hold on power.

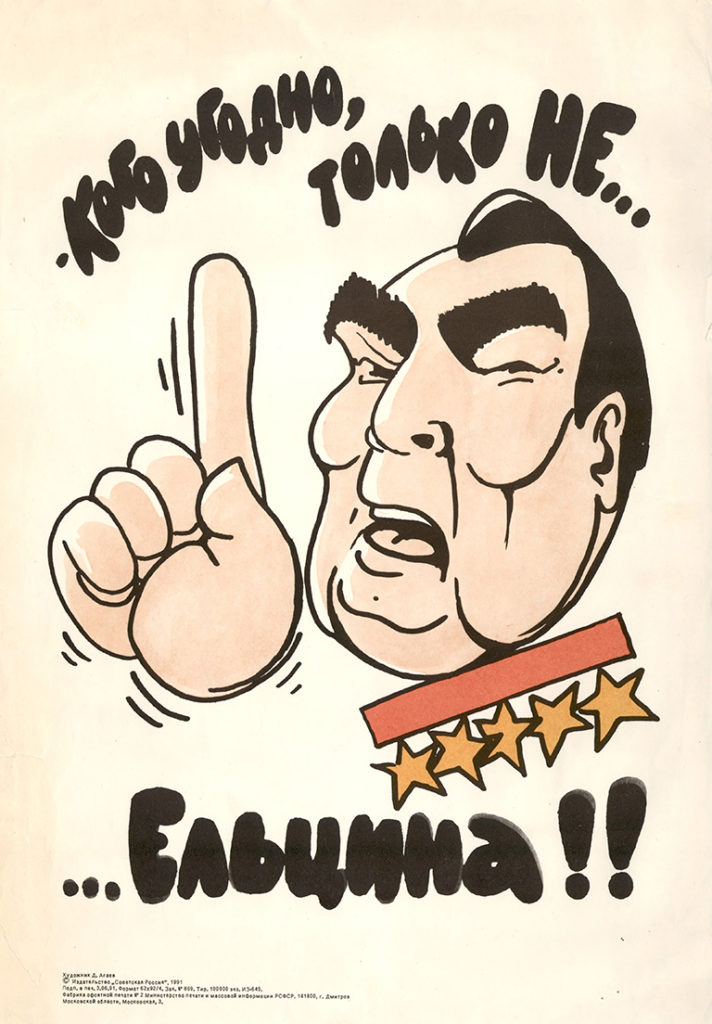

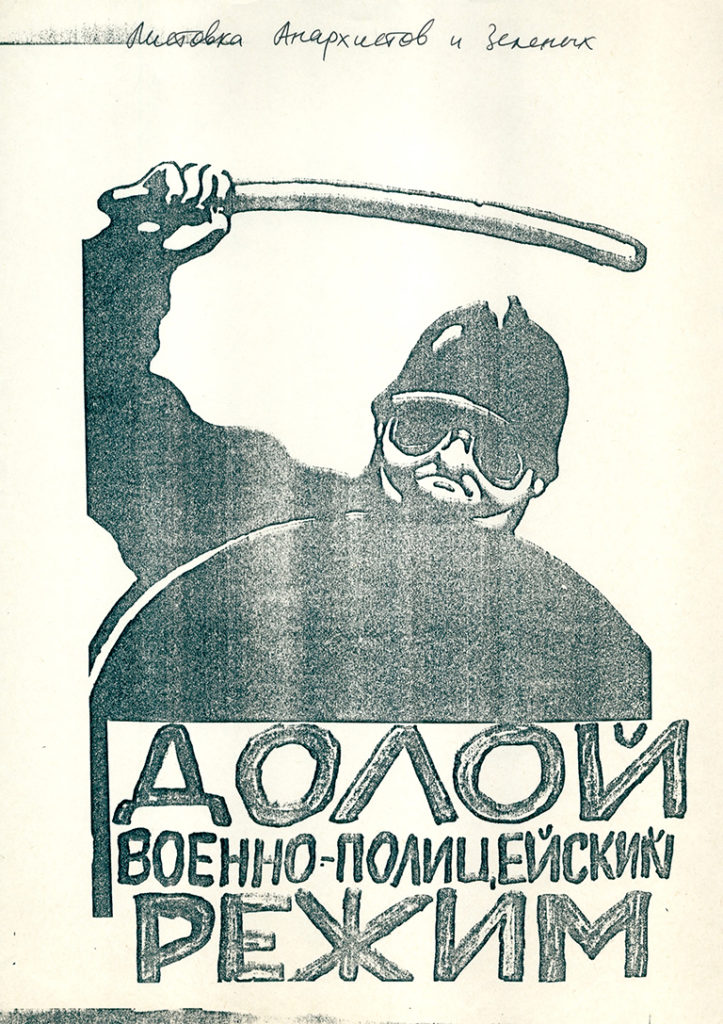

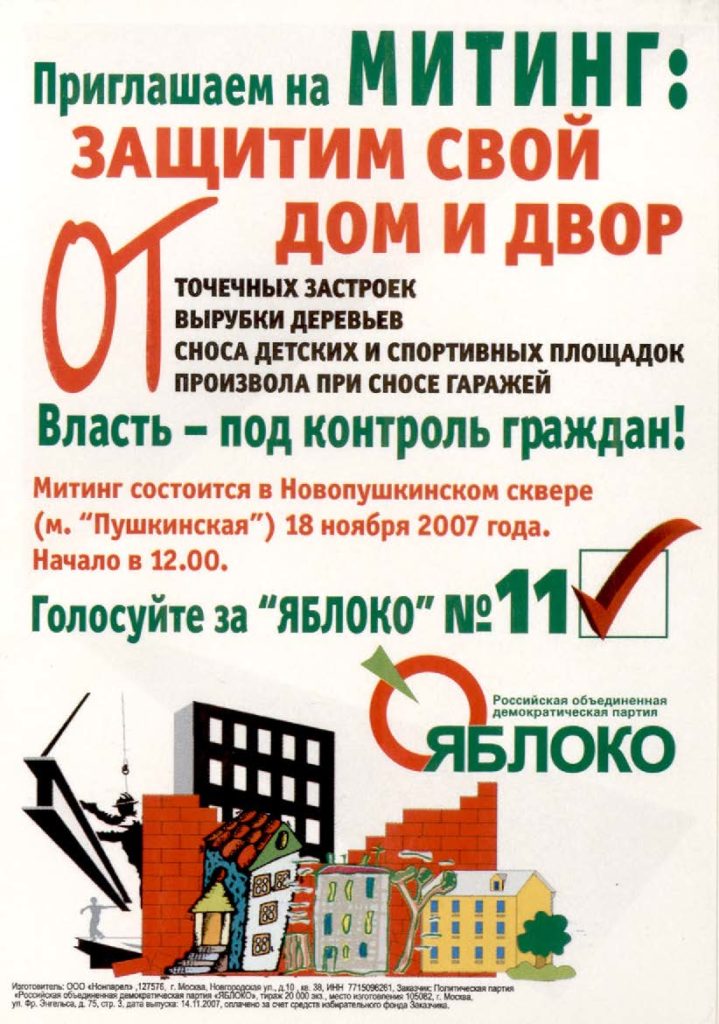

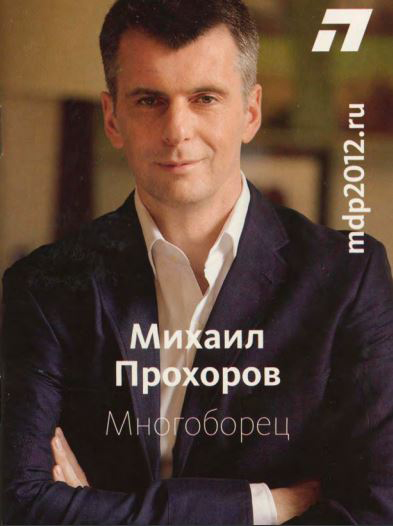

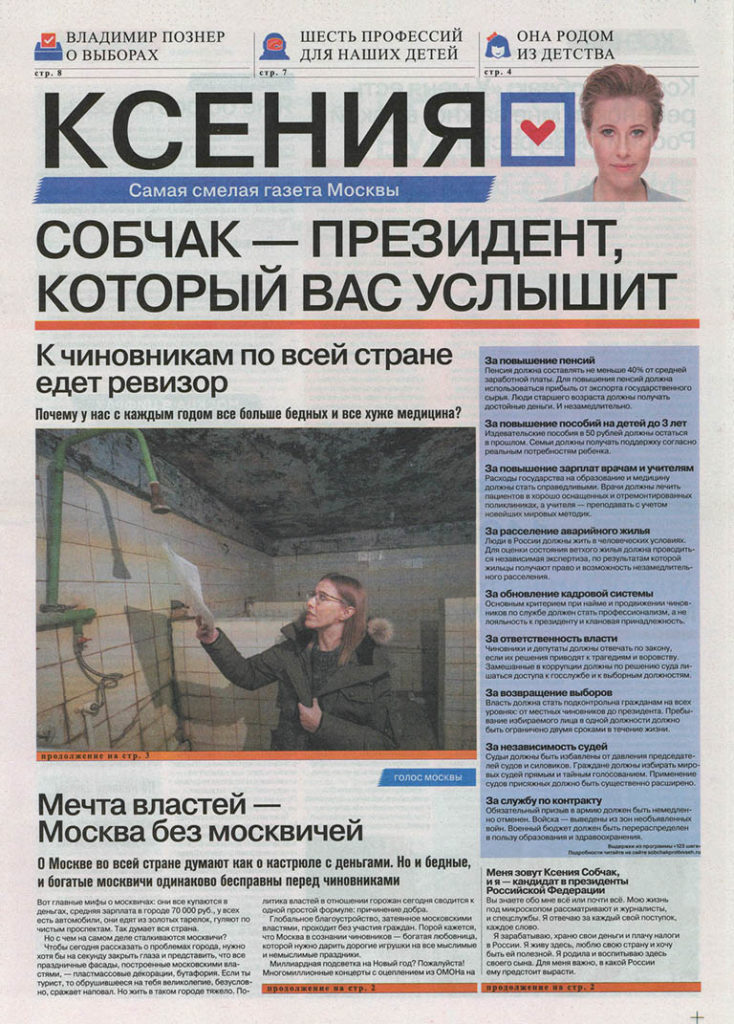

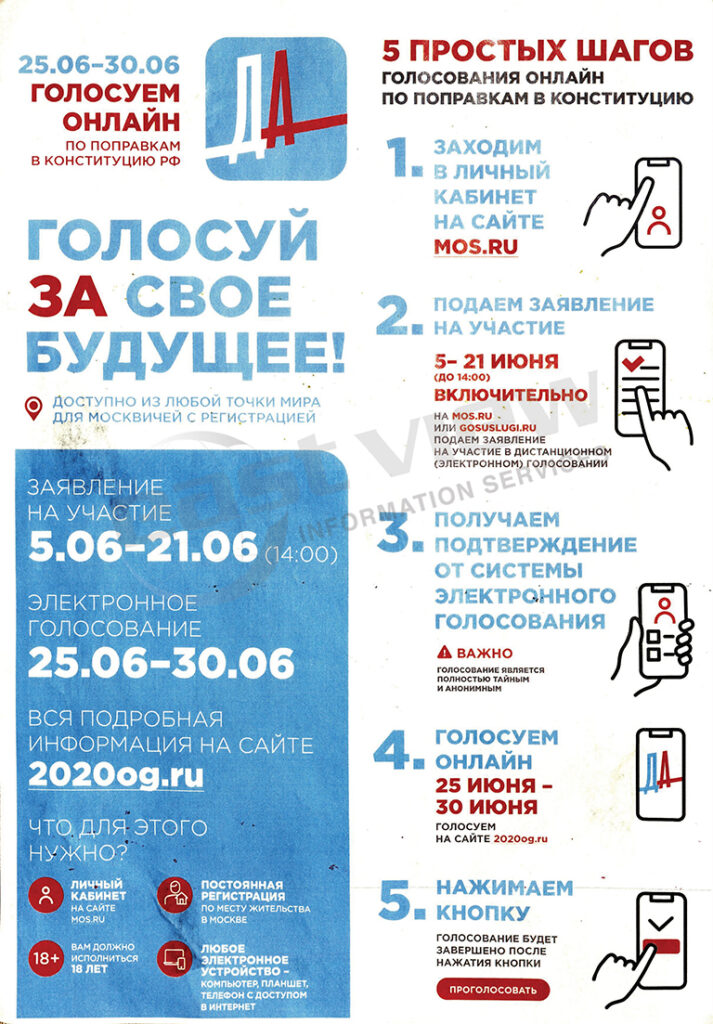

This collection contains unique and rare electoral campaign material produced by a broad range of Russian political parties and opposition groups. It includes special election issue newspapers, party programs, posters, flyers, etc., allowing researchers to delve deep into the election campaigns of various parties and candidates. As such it is an essential resource for understanding one of the most important periods of Russia’s political history and Vladimir Putin’s bid to further consolidate power.